Author: Olga Belyaeva, Advocacy Manager, EHRA, the #Narkonomics movement: from street to government.

The blog is dedicated to our friends and fellows of drug policy reform – “Young Wave” (Lithuania), White Noise (Georgia), Harm Reduction Association Network (Kyrgyzstan), “Your chance” (Belarus), LUNEst (Estonia), Community of people, who use drugs (Kazakhstan) and the Secretariat of the Eurasian Network of people, who use drugs.

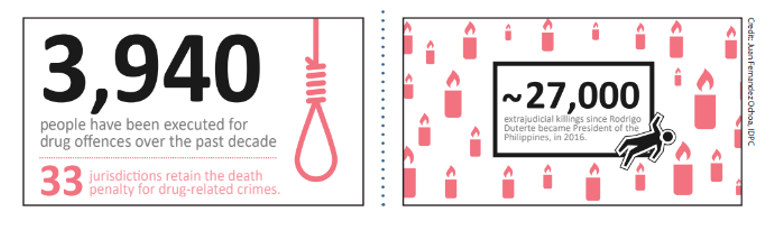

Vienna, 2018 “Do you use drugs yourself?” – a representative of China teasingly asks me at the meeting of the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs. This drug control officer who is convinced of the “effectiveness” of the death penalty for the use and storage of substances. As a result, almost 4,000 people were executed for violations related to substances in 33 jurisdictions of the world. And about 27,000 people were killed without trial in the Philippines[1].

I have been preparing to answer that question since 2004. Dnipro, Ukraine. Kestutis Butkus came from Lithuania to the meeting with drug control having OST medicine in his pocket. It was when our doctor Leonid Vlasenko and I were creating various opportunities for friendly judges and influential police officers to look at the life of drug users from the other, unusual, side. It’s important to consider the theory that harm reduction is valuable but this argument doesn’t make law enforcement think so. The “knowledge” about psychoactive substances and drug users is rooted in our society too deeply. Even the word “methadone” itself provoked aggression among security officers. Everything changed in the moment when Kestutis put on the table what looked like a bottle of water, saying: “Here is methadone, people, it’s like any common medicine”. That was the moment when Kestutis changed the negotiation rules in the hall of the Law Academy with his simple gesture.

I have been preparing to answer that question since 2004. Dnipro, Ukraine. Kestutis Butkus came from Lithuania to the meeting with drug control having OST medicine in his pocket. It was when our doctor Leonid Vlasenko and I were creating various opportunities for friendly judges and influential police officers to look at the life of drug users from the other, unusual, side. It’s important to consider the theory that harm reduction is valuable but this argument doesn’t make law enforcement think so. The “knowledge” about psychoactive substances and drug users is rooted in our society too deeply. Even the word “methadone” itself provoked aggression among security officers. Everything changed in the moment when Kestutis put on the table what looked like a bottle of water, saying: “Here is methadone, people, it’s like any common medicine”. That was the moment when Kestutis changed the negotiation rules in the hall of the Law Academy with his simple gesture.

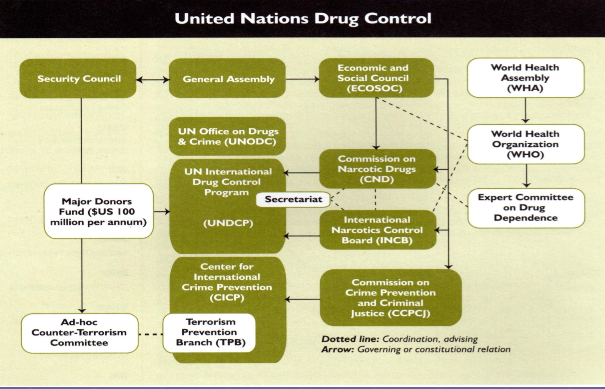

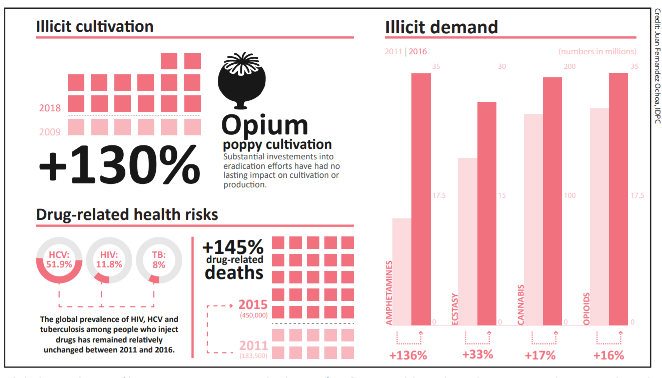

Vienna, 2017 Sergey Bessonov from Kyrgyzstan, Sergey Kryzhevich from Belarus and I are standing in the hall of the 61st Commission on Narcotic Substances and discussing our tasks for the next meetings. We came to see how officials behave during such meetings and listen what they say about the situation in our countries at the international level. The session prepared by the government of Kyrgyzstan should take place tomorrow morning. A representative of Kyrgyzstan delegation approached us while we were standing there, greeted us, showing his surprise at our presence at their “party”.  He gave Sergey an invitation to the session for the next day and told us what they were planning to speak about there. Sergey listened carefully, raised his hand holding the same invitation and said: “Yes, I know about the session of the government of Kyrgyzstan. That’s why I’m here, to listen to your reports.” It was clear for everyone watching that scene and judging from the representative’s reaction that we were at the right place and that it was us who should ask questions and listen to the reports. Because the war on drugs has brought more negative consequences than any other substance, and the work of law enforcement agencies is recognized as unsatisfactory not only by politicians and the Global Commission on Drug Policy, but also by the UN system itself. Ten years ago, 2008 UN Drug Report, as every subsequent report after that, spelled out the negative consequences of the war on drugs: huge illegal black market; organized crime as a threat to security. Criminal organizations have the right to destabilize society and governments. The illicit drug business costs billions of dollars a year, and some part of that money is used to corrupt government officials and poison the economy.[i]

He gave Sergey an invitation to the session for the next day and told us what they were planning to speak about there. Sergey listened carefully, raised his hand holding the same invitation and said: “Yes, I know about the session of the government of Kyrgyzstan. That’s why I’m here, to listen to your reports.” It was clear for everyone watching that scene and judging from the representative’s reaction that we were at the right place and that it was us who should ask questions and listen to the reports. Because the war on drugs has brought more negative consequences than any other substance, and the work of law enforcement agencies is recognized as unsatisfactory not only by politicians and the Global Commission on Drug Policy, but also by the UN system itself. Ten years ago, 2008 UN Drug Report, as every subsequent report after that, spelled out the negative consequences of the war on drugs: huge illegal black market; organized crime as a threat to security. Criminal organizations have the right to destabilize society and governments. The illicit drug business costs billions of dollars a year, and some part of that money is used to corrupt government officials and poison the economy.[i]

Even if officials do nothing to hear us out and invite to the official delegations of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs, our colleagues and partners support us, make security passes for us and share resources with us, even if they have to share their beds to let us in for a night. Engagement with country official delegations is a worthy distribution of drug policy project resources of the Eurasian Harm Reduction Association, Eurasian Network of People who Use Drugs with support from RCNF and the Harm Reduction Consortium, taking into account training during workshops in different countries, opportunities to participate in conferences and meetings of experts on drug policy.

Public organizations didn’t play any part on the stage of international drug control at all 10 years ago. Today we have the opportunity to speak openly on behalf of the community of people who use drugs. When you listen to the reports, different emotions and thoughts arise inside: amount of seized substances, how they seized them, what equipment is needed to identify substances and accuse more people; what is the process of drafting the list of prohibited substances “before they appear in the country”. Visible political pressure on discussions from such countries with murderous drug policy like China, Russia and the States.

Meanwhile our issues are voiced even more often during the plenary sessions, thanks to the progress of Canada in cannabis regulation and harm reduction programs in the EU countries; we are supported by a strong and well-reasoned position of our colleagues from International Network of People who use drugs, International Drug Policy Consortium, Harm Reduction International, Amnesty International, Global Drug Policy Observatory.

At the previous meeting, Oksana Ibragimova talked in her statement about the influence of drug control on attempts to shut down OST sites in Kazakhstan. The data on OST effectiveness is currently being collected again in Kazakhstan in October and November 2018, so once again our organizations invest their time and resources to prove already scientifically proven facts and explain to the officials the value of this program. The system for monitoring negative consequences for people who use drugs is developed in Kyrgyzstan, while the new Code on Misdemeanors and the Criminal Code are introduced. While a moratorium on amendments to the Codes is still working, a group of organizations intending to change the Code, with the leading role of the community of people who use drugs, updated the topic at the national level. The task of EHRA Secretariat is to bring the issues in our countries to the international agenda and to propose solutions based on the needs of people, which are our national partners.

Each of our well-reasoned statements swings the topic to further progress. It is important for us to monitor the process of preparation for the Ministerial Segment in March 2019.

Each of our well-reasoned statements swings the topic to further progress. It is important for us to monitor the process of preparation for the Ministerial Segment in March 2019.

The main conclusion that I made at the meeting of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) is that it’s only possible to change the negotiation rules if you are openly speaking as a person who uses psychoactive substances.

There is no convention that absolves obligations of the countries to maintain and improve the quality of life and health of their citizens. The world will decide the shape of drug policy for the next ten years, from 2020 till 2030, in March 2019.

What position will the representative of your country support during the meetings of the Ministerial segment: human rights and health or violence and corruption?

Check list for the next six months for anyone who wants to change drug policy in their country:

- Study carefully the online course on drug policy Drugs, drug use, drug policy and health

- Read an Advocacy note of our colleagues (IDPC). You will learn that countries have NOT agreed to conduct a reliable assessment of the results and impact of drug policy for 2009-2019, replacing it with the annual report of UNODC. And that report has a lot of problems with data: the questionnaire for countries focuses on process indicators (how many substances were seized, how many people were arrested, etc.). However, this information is not accurate, these data doesn’t come from every country, as the UNODC staff themselves told at the plenary meeting on October 23, 2018. What matters to us is that the data used by UNODC to develop their drug policy plans for the next 10 years don’t show the impact of oppression on the opportunities to exercise the right to privacy, the highest attainable standard of health and well-being for us, drug users and members of our families.

- Address the government and executive power of the country responsible for drug policy with the following questions: the list of members of the country delegation to the high-level meeting in 2018, date and place of the discussions with the community and civil society on the country position that will be presented for voting and will shape the international drug policy for the next decade 2020-2030.

- Prepare the analysis of drug policy in the country, focusing on the issue that most affects the quality of life and health of people who use drugs. Community-led research is our argument in the discussions and gives our position its strength. Research options: Belarus National organization of OST patients “Your chance” on barriers to access and quality of OST treatment, Kyrgyzstan Eurasian Harm Reduction Association on the consequences of the introduction of the new legal Codes in 2019, based on the current situation with fines on the possession of drugs.

…Before asking me whether or not I was using drugs, the representative of the repressive drugpolicy in China had said: “I don’t want to call you a person, who use drugs. I’ll call you a drug user, as it’s written in our resolutions”. (watch the video here)

“I don’t want to call you a person” – this position just shows the essence of oppression: they do not see people of their fates. We are just statistics for them. But in familiar environment. We should make the environment unfamiliar for them to get them our of their smooth way of discussing supply-demand-precursors and international cooperation issues. We should change our approach and play at different levels, using combinations that are different in practice but based on the same values. As I understand, CND has unwritten rules. For example, you can’t call a country by name – no naming and shaming. We have no options here – we should and must tell the names of the countries, otherwise the meaning of the discussion is lost. That is why in our speech we talked about the Estonian practice of referral of detainees for drug-related violations from the police to peer consultants. We talked about the draft law on decriminalization in Georgia, which was stuck in the committees, while people were being deprived of their liberty, family and comfort and imprisoned for 6 years for a sheer amount of 0,0026 grams of methamphetamine. We talked about the situation in Lithuania where, on the one hand, they allowed pills containing cannabis derivates, while the national drug policy is overall repressive. There is no objective to reduce employment opportunities for young people in Lithuania, but this goal was achieved by the criminalization of all types of substances, which resulted in more than 1 400 criminal cases among young people of 18-29 years old in 2017.

As for shaming, it’s not our approach. There are drug policy experts in the room, they are representatives of Canada, the EU, experts from universities and such organizations as IPDC, Amnesty International and other professional organizations. These are people and organizations that influence international drug policy from different sides. It is extremely important for us that these people understand what is happening in drug policy in our countries at the practical level and the cause-and-effect linkage in this regard.

We need to learn directly from other people and get acquainted with the experience of countries such as Canada, Switzerland, Holland, Portugal, the Czech Republic and other countries that allowed decriminalization. People can just grow weed at home or buy it nowadays. In their countries night mayors care about the health of clubbers, support testing on the purity and content of the substances at festivals and in the clubs. And such practice is already helping us: they tell us how and what they do, develop courses on drug policy; analyze endless UN resolutions and protocols, compare and identify contradictions that can help us move forward in our countries and explain to us the essence by preparing analytical notes (see the check list?).

Such statements make other people worry, those people who don’t want to call us people. Because it is officially the statement of the representative of the country about the essence of repressive drug policy, which for many years is covered by the words “preserving the security and well-being of the nation.” The move is made. Calling themselves professionals and using billions to reduce demand and supply of drugs, repressive drug’s control behaves like amateur, stuffed with myths and fears, and completely failed in the results of their work.

Such statements make other people worry, those people who don’t want to call us people. Because it is officially the statement of the representative of the country about the essence of repressive drug policy, which for many years is covered by the words “preserving the security and well-being of the nation.” The move is made. Calling themselves professionals and using billions to reduce demand and supply of drugs, repressive drug’s control behaves like amateur, stuffed with myths and fears, and completely failed in the results of their work.

My answer to the representative of China and repressive drug policy is yes, I use drugs, I enjoy it and I know for sure that the problem is most often in speculation and repressions, and not in substances.

Our time has come. It is time to fundamentally change the approach to drug policy in our countries. We are looking for answers to the questions: who will vote from each country and for what approach in drug policy for the next ten years during the meeting of the ministerial segment in March, 2019. Respond, write, if you are also on topic.

Our time has come. It is time to fundamentally change the approach to drug policy in our countries. We are looking for answers to the questions: who will vote from each country and for what approach in drug policy for the next ten years during the meeting of the ministerial segment in March, 2019. Respond, write, if you are also on topic.

[1] IDPC Shadow report TAKING STOCK: A DECADE OF DRUG POLICY, 2018

[i] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/02/un-war-on-drugs-failure-prohibition-united-nations