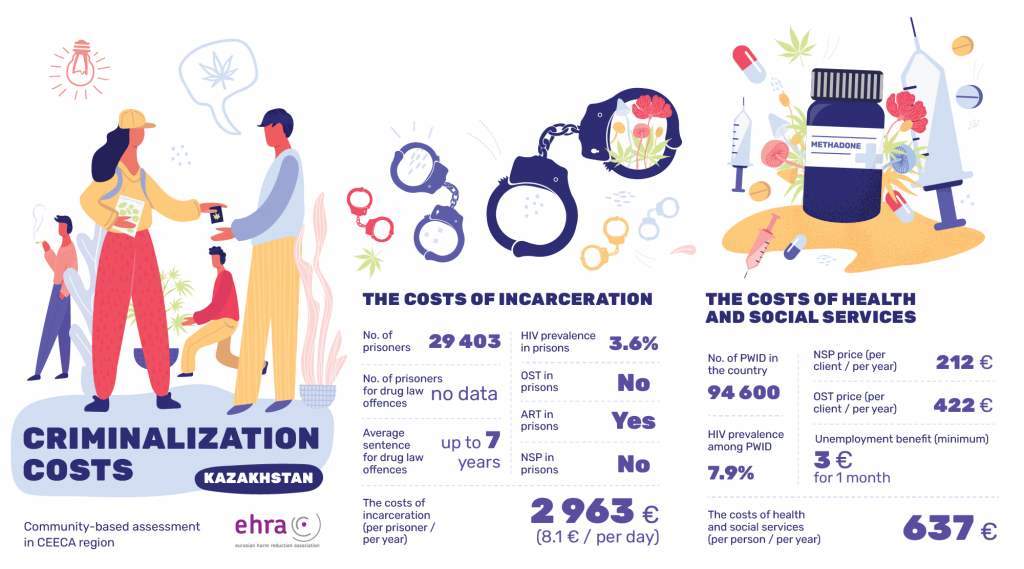

As of March 2020, there were reported to be 29,403 people imprisoned in Kazakhstan [1]. Data on the number of prisoners incarcerated for drug law offences is unavailable, although agencies for internal affairs reported 25,712 offences that were criminal in nature and involved narcotics in the period from 2015 to 2017 (9,250 in 2015; 8,490 in 2016; and 7,972 in 2017), including 9,616 serious drug-related crimes (3,269 in 2015; 3,406 in 2016; and 2,941 in 2017) [2].

Under Chapter 11, criminal infractions against the health of the population and morality, of the Penal Code of Kazakhstan, Article 296.1 states that non-medical use of psychoactive substances in public places is a criminal offense and is punishable by a fine of up to 80 monthly fine units (€430) or correctional labour of the same amount, or involvement in community service for up to 80 hours, or arrest for up to 20 days [3]. Article 296.2 to 296.4 state that the possession of small quantities of psychoactive substances (without intent to distribute) is a criminal offense punishable by a fine of up to 160 monthly fine units (€859) or correctional labour of the same amount, or engaging in community service for up to 160 hours, or by arrest for up to 40 days. Also, the possession of large quantities of psychoactive substances (without intent to distribute) is a criminal offense punishable by a fine of up to 200 monthly fine units (€1,074) or correctional labour of the same amount, or engaging in community service for up to 200 hours, or by arrest for up to 50 days. The possession of psychoactive substances (without intent to distribute) in extremely large quantities is a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment for a term of 3 to 7 years [4]. Furthermore, Article 299.1 states that the habitual use of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances, [and] their analogues, is punishable by a fine of up to 4,000 monthly fine units (€21,480) or corrective labour of the same amount, or community service for a term of up to one thousand hours, or restriction of liberty for a term of up to four years, or deprivation of liberty for the same term [5].

HIV prevalence among prisoners was estimated at 3.6% in 2019 [6] with antiretroviral therapy (ART) available but no opioid substitution therapy (OST) nor needle/syringe programmes (NSP) are available in any Kazakh prison [7].

It costs the Government of Kazakhstan €2,963 per year to keep one person in prison, or €8.1 per month [8].

In 2020, there were estimated to be 94,600 people who inject drugs in Kazakhstan [9] with a HIV prevalence reported in 2019 of 7.9% [10]. NSP costs €212 per client, per year [11] and OST €422 per client, per year [12]. Unemployment benefit is only available to citizens whose employers have made appropriate social payments to the State Social Insurance Fund (SFSF) and unemployment benefits cannot exceed 40% of lost income and is based on income from the previous 2 years. The duration of payments into the SFSF determines how quickly the unemployment benefit will be paid to the individual with the amount being €3.36 for one month [13].

Therefore, if the Government of Kazakhstan were to cover all the costs of assisting a person who injects opioid drugs in community settings, the total would be €637 per year compared with €2,963 to have that person in prison. Consequently, decriminalising drug use and possession would save the Government of Kazakhstan €2,326 per person each year.

[1] World Prison Brief. Kazakhstan. London; Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research, University of London. https://www.prisonstudies.org/country/kazakhstan (accessed 7 August 2021).

[2] Replies of Kazakhstan to the list of issues. Sixty-fifth session, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, United Nations Economic and Social Council, E/C.12/KAZ/Q/2/Add.1, 13 December 2018. (accessed 7 August 2021).

[3] Ministry of Justice. Penal Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 3 July 2014. Nur-Sultan; Institute of Legislation and Legal Information. https://adilet.zan.kz/eng/docs/K1400000226 (accessed 7 August 2021).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Op.cit.

[6] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS). The Key Populations Atlas. Geneva; UNAIDS. https://kpatlas.unaids.org/dashboard (accessed 3 August 2021).

[7] Harm Reduction International (HRI). Global State of Harm Reduction 2020, Regional Overview 2.2 Eurasia. London; HRI, 2021. https://www.hri.global/files/2020/10/26/Global_State_HRI_2020_2_2_Eurasia_FA_WEB.pdf (accessed 3 August 2021).

[8] Mikhailova A., Ibid.

[9] Kazakh Scientific Centre of Dermatology and Infectious Diseases. Global Monitoring of the AIDS Epidemic 2020. Country progress report – Kazakhstan. Almaty; Kazakh Scientific Centre of Dermatology and Infectious Diseases, 19 March 2020. http://www.kncdiz.kz/files/00007836.pdf (accessed 7 August 2021).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Information submitted by national partners.

[12] The Economist Intelligence Unit. Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: The economic, health and social impact. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited, 9 March 2021. https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/sites/default/files/eiu_aph_investing_hiv_launch.pdf (7 August 2021).

[13] NUR.KZ. Unemployment benefits in Kazakhstan: the amount and timing of payment in 2021. Almaty; NUR.KZ, 13 January 2021. In Russian. https://www.nur.kz/fakty-i-layfhaki/1713462-posobie-po-bezrabotice-v-kazahstane-summa-i-sroki-vyplaty-v-2021-godu/ (accessed 7 August 2021).