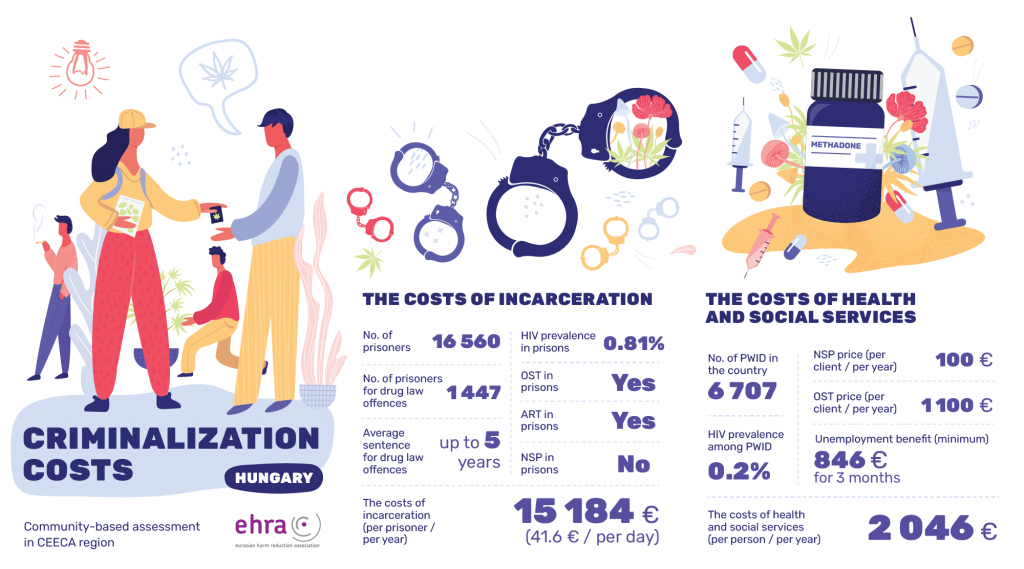

In 2019, there were 16,560 prisoners in Hungary, of which 1,447 were imprisoned for drug law offences [1]. Drug consumption is a criminal offence punishable by up to 2 years in prison as is drug possession if it involves only small quantities. Sentences of between 5 and 15 years are given if offences involve a larger quantity of drugs. For new psychoactive substances (NPS), the Criminal Code now provides for up to 3 years for possession of more than a small amount (2 grams of the active substance). For possession of a small amount, the user will be subject to a non-criminal infringement procedure. As of 2013, maximum penalties are no longer lower for offences committed by people who use drugs, though the court may take the person’s drug use into consideration when sentencing. The option to suspend prosecution in the case of treatment is available to offenders committing drug law offences that involve only small quantities of drugs (production, manufacture, acquisition, or possession for personal use); this option is not available within 2 years of a previous suspension [2].

HIV prevalence in prisons was estimated in 2013 at 0.81% [3] with antiretroviral therapy (ART) reportedly available to prisoners as is opioid substitution therapy (OST) [4]. According to Order no. 38/2015. (V.20.), all detention facilities must ensure methadone treatment as a therapy option for opioid dependence if the continuation of methadone treatment is indicated by the specialised outpatient treatment centre treating the individual before s/he was admitted to the detention facility, or if it is recommended by a specialist at the National Institute for Forensic Observation and Psychiatry and the affected person gives his/her written consent. The treatment must be carried out at such therapeutic sites which are designated for acquiring, storing and using methadone, for which prison institutions are not entitled due to the lack of an operating license. Consequently, prisoners have to be transported to a designated specialised outpatient treatment centre or dependence or psychiatric unit in the region to provide OST. According to data from prison institutions in 2017, OST was available in 1 prison and at 4 others it was provided by an external service provider. There were 8 detainees in receipt of OST (methadone or suboxone) prior to being admitted to prison, among them two (in separate institutions) continued OST after incarceration. In previous years, OST was occasionally provided by external service providers if requested by a detention facility, but the number of such cases was exceptionally low [5]. However, no needle/syringe programmes (NSP) exist in Hungarian prisons [6].

The cost to the Government of Hungary of each prisoner is €15,184 per year, or €41.60 per day [7].

There were an estimated 6,707 people who inject drugs in 2015 in Hungary and recent studies have indicated that there has been a shift from injecting established drugs (heroin and amphetamines) to injecting NPS (largely synthetic cathinones) [8]. HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs in community settings was estimated in 2015 as being 0.2% [9].

The costs of NSP services in 2018 were estimated at €100 per client, per year, and OST at €1,100 per client, per year [10]. Unemployment benefit is paid for 3 months at the rate of €282.02 per month, or €846.06 for the full 3 months; this equates to 60% of a person’s previous average pay but is capped at no higher than the national minimum wage of HUF167,400 (or €470) per month [11].

Therefore, it costs the Government of Hungary €2,046 per year to assist a person who injects opioid drugs in community settings, whereas to imprison that person costs the government €15,184 per year. Consequently, decriminalisation of drug use and possession would save the state €13,138 for each person who injects drugs who is imprisoned. Based on the number of people in prison for drug law offences, total savings to the Government of Hungary could be as high as €19 million per year.

[1] Aebi MF, Tiago MM. SPACE I – 2019 – Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics: Prison populations. Strasbourg; Council of Europe, 2020. https://wp.unil.ch/space/files/2021/02/200405_FinalReport_SPACE_I_2019.pdf (accessed 4 August 2021).

[2] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Hungary Country Drug Report 2019. Luxembourg; Publications Office of the European Union, 2019. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/11332/hungary-cdr-2019_0.pdf (accessed 7 August 2021).

[3] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). World Drug Report 2015. Vienna; UNODC, 2015, Chapter 7.2. https://www.unodc.org/wdr2015/field/7.2._HIV_and_hepatitis_among_people_held_in_prisons.xlsx (accessed 7 August 2021).

[4] Harm Reduction International (HRI). Global State of Harm Reduction 2020, Regional Overview 2.2 Eurasia. London; HRI, 2021. https://www.hri.global/files/2020/10/26/Global_State_HRI_2020_2_2_Eurasia_FA_WEB.pdf (accessed 3 August 2021).

[5] Information on the availability of OAT in prisons was provided by the Hungarian National Focal Point.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Aebi M F, Tiago MM. SPACE I – 2020 – Council of Europe Annual Penal Statistics: Prison populations. Strasbourg; Council of Europe, 2021. https://wp.unil.ch/space/files/2021/04/210330_FinalReport_SPACE_I_2020.pdf (accessed 3 August 2021).

[8] EMCDDA, Ibid.

[9] EMCDDA, Op.cit.

[10] Information submitted by national partners.

[11] Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. Hungary – Unemployment benefits. Brussels; European Commission, undated. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1113&langId=en&intPageId=4584 (accessed 7 August 2021).