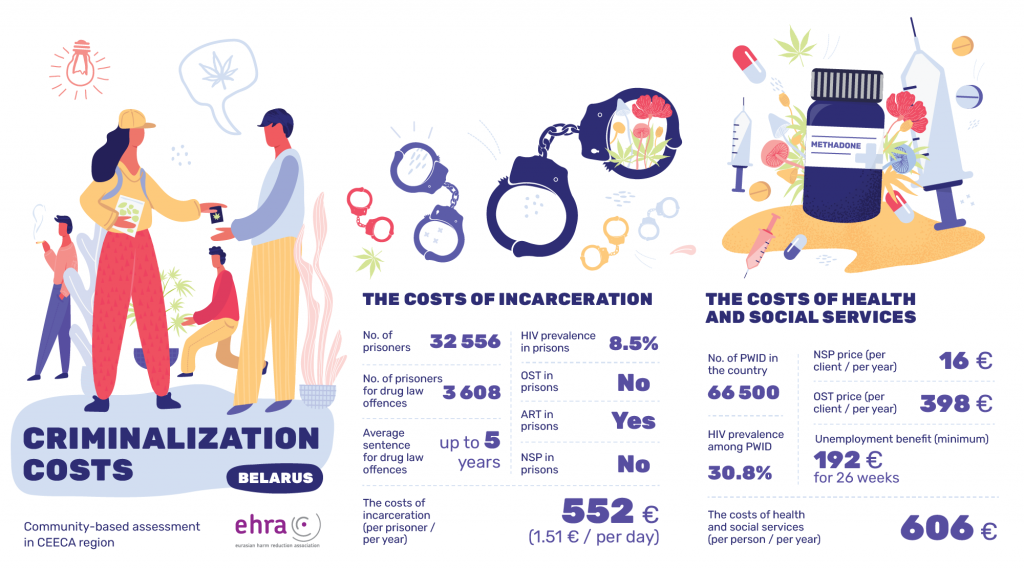

As of 2018, there were 32,556 prisoners in Belarus [1], of which 3,608 (11%) were imprisoned for drug law offences as of 2016 [2]. Such drug law offences can result in imprisonment of up to five (5) years for drug possession and up to 25 years for serious drug-related offences [3]. If a crime is committed by a person who is drug dependent, the court may sentence the individual to imprisonment with mandatory treatment while inside prison [4].

HIV prevalence among inmates is estimated at 8.5% [5] and antiretroviral therapy (ART) is reported to be available [6] but opioid substitution therapy (OST) and needle/syringe programmes (NSP) are not available in prisons [7].

Incarceration costs the government of Belarus €552 per inmate, per year, or €1,51 per day [8].

There were an estimated 66,500 people who inject drugs in the country in 2019 [9] with an HIV prevalence of 30.8% [10]. The average cost of NSP is €15.64 per client, per year [11] and €398.79 per client, per year for OST [12]. Average unemployment benefit is €191,88 for 26 weeks, or €7.38 per week [13].

Consequently, Belarus remains the only country in CEECA region where incarceration costs are lower than the cost of health and social services for people who use drugs, with the average cost to the government of €798.19 per year to support a person who injects drugs in community settings versus €552 per year to imprison such a person. The lower incarceration cost could be explained by very poor and degrading conditions in prison settings.

[1] World Prison Brief. Belarus. London; Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research, University of London. https://www.prisonstudies.org/country/belarus (accessed 4 August 2021).

[2] Gubskaya S. Let them pray for death. Belarusian war on drugs. Political Critique, 2 February 2018. http://politicalcritique.org/cee/belarus/2018/let-them-pray-for-death-belarus-war-on-drugs/ (accessed 4 August 2021).

[3] Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). Foreign travel advice, Belarus. London; FCDO. https://www.gov.uk/foreign-travel-advice/belarus/local-laws-and-customs (accessed 4 August 2021).

[4] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Belarus Country Overview. Lisbon; EMCDDA, undated. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/country-overviews/by#nlaws

[5] Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS). The Key Populations Atlas. Geneva; UNAIDS. https://kpatlas.unaids.org/dashboard

[6] UNAIDS, Ibid.

[7] Harm Reduction International (HRI). Global State of Harm Reduction 2020, Regional Overview 2.2 Eurasia. London; HRI, 2021. https://www.hri.global/files/2020/10/26/Global_State_HRI_2020_2_2_Eurasia_FA_WEB.pdf (accessed 3 August 2021).

[8] https://news.tut.by/society/519227.html?crnd=87915

[9] Parsons D, Burrows D, Falkenberry H, McCallum L. Regional Analysis: Assessment of HIV Service Packages for Key Populations in Selected Countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Washington DC; APMG Health, April 2019. (accessed 9 August 2021).

[10] HRI, Ibid.

[11] Information submitted by national partners and applies only in Gomel area.

[12] Kralko AA. Аssessment of the sustainability of the opioid agonist therapy programme in the context of transition from donor support to domestic funding in Belarus. Vilnius, Eurasian Harm Reduction Association, 2020. https://old.harmreductioneurasia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/EHRA-OAT-Sustainability-Assesment-Belarus-ENG-2020.pdf (accessed 4 August 2021).

[13] My own lawyer. Unemployment benefit amount. http://samsebeyurist.by/spravochnaya-informatsiya/razmery-pensij/posobij-po-bezrabotice (accessed 4 August 2021).